Introduction

The condensed power of four Chinese characters can illuminate and challenge many Western hopes for genuine globalization and for the inclusion of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime into peaceful collaboration. 卧薪尝胆 wo xin chang dan ("sleep on straw, suck on sorrow") appears at first as a seemingly innocuous proverb from ancient history: King Guojian, in the fifth century BCE, had become a prisoner of a man who destroyed his country. Humiliated by eating excrement, the king was finally released. Vengeance was never far from Guojian's mind. Sleeping uncomfortably on the floor and taking sips from a bag of bile kept up his courage until he finally marshalled an army that defeated and took over the enemy state.

This is no quaint story about ancient warlords. 卧薪尝胆 wo xin chang dan became a central theme in Chinese nationalism in recent years, increasing in potency during the era of Xi Jinping and the cult of国耻 guochi ("national humiliation").[1]The goal of such sayings is to portray China as weak and vulnerable, despite its obvious wealth and influence on the global stage. It is meant to convince the Chinese people that in order to avert a constant threat of dismemberment and disgrace, China has to be kept unified at all costs. For modern China, one of the lessons of ancient history dating back to the First Emperor, Qin Shihuang, who conquered most of China in 221 BC, is that unity requires uniformity in thought, in culture and in physical space. According to the narrative of "national humiliation," only a strong – indeed, draconian – regime can impose unification, which depends on a lack of troublesome diversity.

In the early 1970s, Mao Zedong (1893-1976) had perhaps overplayed his political hand by an unqualified admiration for the brutal, murderous Qin Shihuang – a key figure for political study toward the end of the Cultural Revolution. Xi Jinping, a follower of Mao since 2013, speaks less about enforced uniformity of thought and more about "harmonizing" Chinese and global outlooks. This softer term nonetheless insists on shaping a worldview that accords with the ongoing sovereignty of the CCP. Within China today, given the threat of COVID and shortages created by antagonism with Australia and the U.S., the need for emphasizing nationalism has become more and more acute. Sucking on bile is not just an old strategy that worked for Guojian. Rather, as Jocelyn Eckberg pointed out in the state-sponsored China Daily, 卧薪尝胆 wo xin chang dan provides "spiritual solace... never forget humiliation... until the Kingdom emerges as a strong and prosperous nation."[2]

The regime of Xi Jingping has made it its business not to have the tale of Guojian be merely "spiritual solace." It has become an essential core of爱国教育aiguo jiaoyu ("Patriotic Education"). 爱国 aiguo means to love the nation in an intense, devoted fashion more often associated with spouses and family. The subtext is never obscure: To love the country means to love the CCP, pure and simple. There is no room for dissent under this doctrine. It is only conformity to the reigning powers that is keeping China united in a dangerous and carnivorous world.

Worries About Divvying Up The Chinese "Cake"

The popular TV series "The Great Revival," created in 2007, retold the story of Guojian with clearly patriotic emphasis. While bile and straw make their due appearance, what matters most is not the warrior's asceticism. Rather, it is his unquestioning devotion to the goal of national unity. A weak and vulnerable China can only maintain its territorial integrity by squashing all "selfish" concerns (and dissent) – a theme also emphasized in the 2002 Chinese prize-winning movie "Hero," which was directed by the rather open-minded Zhang Yimou.

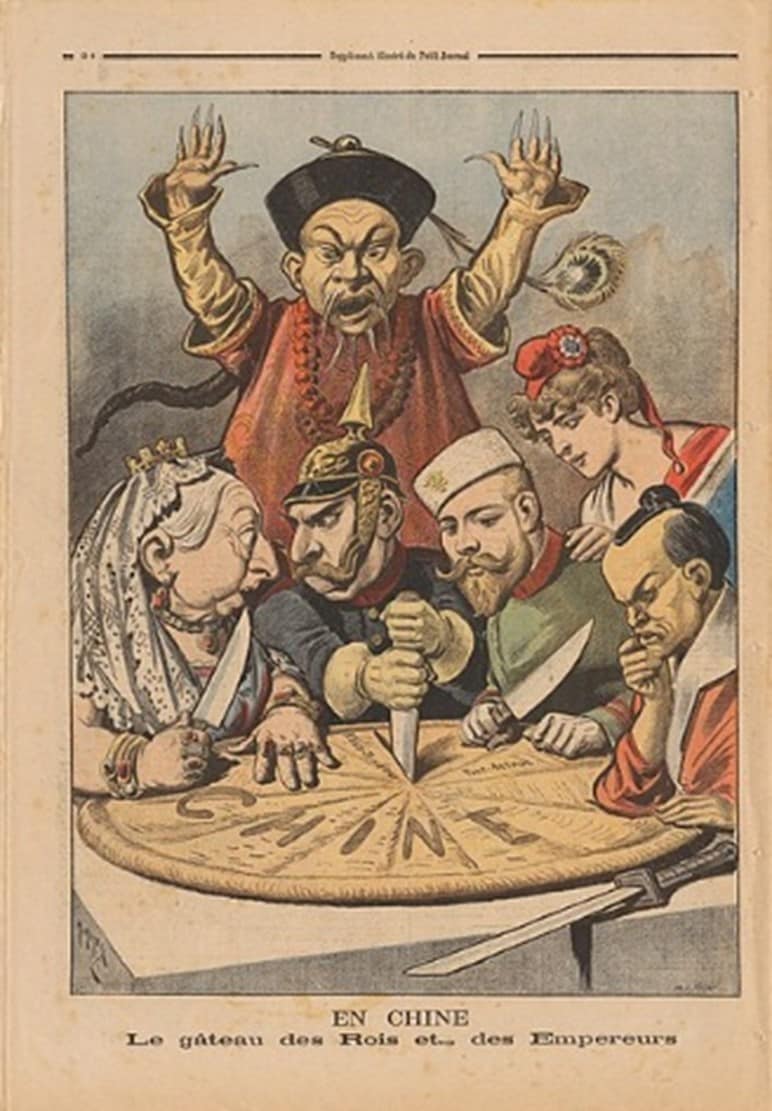

The regime of Xi Jinping has been able to mobilize disparate cultural resources to enforce this vision of a fragile country which needs the absolute loyalty of all its citizens. "Patriotic Education" in Xi's China has made ample use of European cartoons critical of Western imperialism. One of the most frequently used images is one published in France in Le Petit Journal on January 16, 1898 showing China as a pie being apportioned by foreign countries.[3]

(Source: Le Petit Journal via the Library of Congress)

Three years after China's defeat by Japan in 1895, the foreign powers took advantage of the weakness of the Qing dynasty to carve out special spheres of influence. This vicious image of the "Chinese cake," mind you, already ruled by Manchu invaders since 1644, is dramatized by the butchering knife in the hand of Kaiser William II, while Queen Victoria and Czar Nicholas II each struggle to get a piece as well. The Meiji Emperor, who will have the greatest impact on China's fate in the 20th century, contemplates a better strategy to be achieved by his samurai sword. A helpless ghost-like figure hovers in the background, unable to stop the ravage despite his culture-cultivated long nails and Manchu-imposed hair style of the queue.

Patriotic young Chinese are not told much about the corrupt native regime that led to the military weakness of the Qing dynasty. What matters is Western rapacity – the endless quest to take food from the mouths of hungry, impotent Chinese.

An earlier illustration made by Honoré Daumier in 1859 became even more popular. Circulated at a time when the French prepared to ally with England for the siege of Beijing, this image shows not the West's imposing diplomatic relations with the Qing, but rather the old tribute system. To prepare for this expedition, the French, like the British, used opium as cash in China. Just a few months before they shared in the looting of the Yuan Ming Yuan Summer Palace in 1860, Daumier portrays a French officer shoving the deadly narcotic down the throat of a powerless Chinese.[4]

(source: Honoré Daumier via Brandeis IR)

The sadistic image is especially popular in "Patriotic Education" schoolbooks because it evokes ire and a fierce desire to protect and rescue the victims of imperialism. As with other images, there is no discussion of the Qing dynasty's corruption, which led to the wide-spread addiction to opium, first among the elites, and then later among the common folk. The wide availability of foreign and home-grown narcotics at that time does not explain why masses of Chinese chose to buy and consume them. Historian Jonathan Spence pointed out in his 1998 essay on "Opium Smoking In China" that there were complex internal factors that led to mass addiction during the Qing dynasty.[5] Willful disregard of such factors helps to make opium the symbol of the "bile" – of that bitter humiliation that must be constantly remembered in order to buttress national pride and support for the communist regime.

Consuming "Wolf's Milk"

Documenting the corrosion of legitimacy from within China is not convenient for the purpose of the government's "Patriotic Education"; it is better to dwell on victimization from without. The destruction of the Summer Palace is one key motif in the narrative of China's disgrace at the hands of imperialism. This ravage is often linked to the suppression of the native Boxer Rebellion in 1900 as another example of vicious foreign intentions that threaten China's unity.

To challenge these narratives is to draw attention to the wide-spread distortion of historical truth in public education, especially regarding facts about native violence and oppression. One common phrase for this strategy of obfuscation is 狼奶 lang nai ("wolf 's milk"). In 2006, historian Yuan Weishi dared to write about this predicament in the following words: "We grew up drinking wolf's milk. In looking through middle school history texts, our youth are still drinking wolf's milk."[6]

Yuan's critique of miseducation appeared in an essay about Chinese brutalities during the Boxer Rebellion. It was published in a popular youth journal called Bing Dian ("Freezing Point"). Within a month, the journal was shut down, but Li Datong, editor of Freezing Point, did not let himself be frozen out without protest. He wrote a letter of dissent and posted it on the Internet. He pointed out that the CCP's reaction was proof of its strategy of nurturing the masses on "wolf's milk," and wrote: "When one does not have the truth, one is afraid of debates; when one does not have truth, one is afraid of openness."[7]

Ostracized by CCP journals, Yuan Weishi and Li Datong were pushed out of public discourse. Other intellectuals, most notably Liu Xiaobo, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, suffered far more by being jailed and persecuted to death for refusing to drink "wolf's milk" – especially when they challenged more recent atrocities committed by the communist regime, such as the suppression of the Tiananmen movement in 1989.

Where does one go to consume "wolf's milk"? In the last decade, the marble remains of Jesuit-built palaces for the Manchu rulers have become a major site for the performance of loyalty rituals demanded by the CCP. Every year, the month of October brings not only celebrations of the victory of the CCP, but also obligatory visits to sites that bear witness to Western rapacity. The narrative of such pilgrimages combines the Franco-British expedition of 1860 with the 1898 fight over foreign concessions as well the 1900 march upon Beijing by eight allied nations united in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion. The 40-year timespan, the disparate circumstances, and Qing's own violence against foreigners are not mentioned.

Truth and this cult of national humiliation are diametrical opposites. What matters in today's China is total devotion to the regime which dwells upon the familiar slogan: 在也不zai ye bu ("never again"). This rallying cry demands and reinforces the CCP view of history and of China's endangered place in the world. The emphasis of "Patriotic Education" is on The Hundred Years of Humiliation, the title of the first of many such books on this theme authored starting in 1997.[8] The goal is to create an emotionally charged and infuriating narrative about all the disgrace heaped upon China from the Opium War of 1840 to the Communist victory in 1949.

The celebration of 国耻节guochijie ("National Humiliation Day") is a CCP-orchestrated annual ritual. Sometimes this takes place at the ruins of Yuan Ming Yuan, sometimes at the Nanjing Massacre Museum, more recently at the Mukden Museum for National Humiliation – a site marking the start of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931.[9] Sites and dates have varied over the past decade, but not the message. Xi Jinping, while proclaiming to the international media the importance of peaceful globalization, forces Chinese youth to dwell on humiliation and to rally around the red flag of the CCP.

For example, in December 2020 China's Harbin Institute of Technology required its graduate and post graduate students to take part in a rather militaristic commemoration of the "Shame of September 18, 1931." The goal was explicitly to sear into the consciousness of future leaders of the economy the importance of atrocities against China. Dwelling at length upon Japanese experiments with biological warfare in Manchuria, the party secretary urged students to "never forget national humiliation."[10] Dioramas, such as the one below from the Mukden Museum forced viewers to imagine themselves enchained, abused, and dismembered by brutal outsiders.

(Source: 9.18 Mukden Incident Museum)

The final goal, of course, is not despair or the desire to vomit out such horrific scenes. Rather, in the words of the party secretary: "History needs to be remembered and it must lead to a long-term vision. Student Party members must always follow the guidance of the Central Party Committee's spirit, be patriotic and lead their classmates and families to help realize the Chinese Dream."[11]

How much this dream depends upon continued portrayals of China as both vulnerable and invincible will be the subject of future essays. For now, there is no room in China's public forums to discuss the dangers of "drinking wolf's milk." Instead, the heroes of the day are the Wolf Warrior[12] diplomats who keep barking harshly against Australia and the USA. Under Xi Jinping, high level foreign service officers have been encouraged to use confrontational tactics to combat all criticism of CCP policies in handling COVID, Hong Kong, internal dissent, or international conflicts. Modeled on a brutally patriotic film, "Wolf Warrior 2," this style of diplomacy fights against any perceived weakness or criminality attributed to the regime.[13]

If the nation is not portrayed as endangered, what reasons would there remain for the fiercely imposed uniformity of thought? It is only the dread of national disintegration that keeps many Chinese from speaking out about the "Second Century of National Humiliation"[14] – a reference to the atrocities of the Communist regime itself that can be found in dissenting forums. Historians and netizens in China estimate that close to 80 million lives have been cut short by CCP-sponsored policies since 1949.[15] The cumulative grief and trauma of these tragedies cast a heavy shadow around the gilded edges of Xi Jinping's China Dream.

*Vera Schwarcz is a Special Advisor to MEMRI. She is Emerita Professor at Wesleyan University and a Senior Researcher at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

[1] Paul Cohen, Speaking to History: The Story of King Guojian in Twentieth-Century China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009)

[2] Jocelyn Eikenburg, The humble power of sleeping on sticks and tasting bile, China Daily Global, June 5, 2020.

[3] This image, its subsequent impact is discussed by Rudolf G. Wagner in his essay "Dividing up the (Chinese) Melon: The Fate of a Transcultural Metaphor in the formation of a National Myth," The Journal of Transcultural Studies 8:1, 2017. Importantly, Wagner points out that the image published in France gained more popularity in China as guafen瓜分 " carving up the melon" – more readily understood by common people whose sentiments are to be whipped up for the sake of "national humiliation."

[4] This image and its historical context is discussed by Stephen R. Platt, Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age, New York: Knopf, 2018.

[5] Jonathan Spence, "Opium Smoking in Ch'ing China" European Intruders and Changes in Behavior and Customs in Africa, America and Asia before 1800, New York: Routledge, 1998

[6] Quoted and discussed by Charles W. Hayford, "The High School History Textbook Debate in China," History News Network, April, 2006.

[7] Li Datong's letter and the suppression of Bing Dian is discussed in: Vera Schwarcz, "Truthfulness at Night, Truthfulness at Dawn: Reflections on a Common Striving in Chinese and Jewish Traditions," Journal of World History 19:4, 2008.

[8] He Yu's book and its subsequent impact of Chinese politics is the subject of: Zheng Wang, Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations, New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

[9] Opened in September, 1991, this Museum has become more and more central for the marking of the "National Day of Humiliation." Located originally on the site of the bombing that launched the Japanese conquest of Manchuria, it is marked by a huge memorial in shape of a calendar (18 meters high and 30 meters wide), riddled with bullet holes to symbolize the cruelty of the war. On the right side of the calendar is carved the message: "When national tragedy strikes, the people rise up and fight." For a further discussion of the ambiguities and half-truths embodied in this museum and others like it, see: Kirk A. Danton, "Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums" The Asia-Pacific Journal 5:10, 2007.

[10] 学习贯彻全会精神,赓续奋斗新百年 (Learn and implement the spirit of the plenary session and continue to struggle for a new century) 2020-12-15, 环境学院

[11] Ibid.

[12] See MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis Series No. 1535, Veteran Chinese Diplomat Yuan Nansheng: 'Wolf Warrior' Diplomacy Will Not Give China Victory Over U.S.; We Must Keep A Low Profile With The Sword In The Scabbard As In Deng Xiaoping's Guiding Ideology, October 14, 2020.

[13] Nakazawa Katsuji, China's 'wolf warrior' diplomats roar over Hong Kong and the world, Nikkei Asia Review, May 28, 2020.

[14] Ted S. Yoho, China's Second Century of Humiliation, The Diplomat, June 25, 2018.

[15] Yang Jisheng, former CCP journalist, turned historian has authored two explosive, detailed historical studies: Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine 1958-1962 (New York, 2012) estimates that 30 million people died of starvation and another 46 million suffered unnatural death. Yang's latest book to be translated into English, The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Cultural Revolution (New York, 2020) estimates at least1.5 million were killed during the Maoist persecutions of the 1960s. Yang's two books do not include (yet) other Communist Campaigns such as collectivization and the Anti-Rightist Movement of 1957 which claimed many more lives as well. In additional to Yang's copiously documented books, Chinese netizens have been using the Party's own propaganda about "national humiliation" to challenge the regime for its atrocities against ordinary citizens such as Dr. Li Wenliang, arrested for spreading "rumors" about COVID in the spring of 2020. "This is the real guochi!" https://twitter.com/lengshanshipin/status/134420106854907520, December 30, 2020. Another a tweet argued: "The Chinese Communist Party has established an illegal regime for more than 60 years. It has directly and indirectly massacred 80 million Chinese people. Its crimes against humanity far exceed those of the Nazis." https://twitter.com/2019nCoVRec2/status/1344134309041467393, December 30, 2020.