One of the overarching challenges of the so-called Global War on Terror after September 11, 2001 was that while the terrorist groups that attacked us that day were quite small, they embedded themselves and sought to closely cleave their identity to a billion-strong global religion. All of the Al-Qaeda fighters (and later ISIS terrorists) were Muslims, but statistically speaking very few Muslims were Al-Qaeda or ISIS. This meant that governments fighting the terrorists always had to weigh how their actions could differentiate between Muslims and the terrorists. The terrorists themselves would play this deadly game, seeking to propagandize whatever action or policy being implemented as directed not against them alone but against Islam and Muslims as a whole. That was the logic behind such clumsy terms of art such as "Countering Violent Extremism" (CVE) and using the term "Daesh" rather than saying "Islamic State" (to avoid using the word Islam).

So, the challenge for the West and its partners in the Muslim world was to define the circle broadly enough to address the threat but narrowly enough so that the appeal of the extremists would not be able to jump into the mainstream, into a potentially much larger host population. This was a difficult task, and counterterrorism practitioners, in my view, never got it right, because it was and remains difficult. Is the enemy a Salafi or a Salafi-jihadi? Is the danger "extreme" opinions (defined by whom exactly?) or extreme – violent – actions? What was the difference between a Yemeni tribal fighter, with his conservative views and martial values, and an Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) fighter? Seen from a Predator drone both looked very similar.

This is why the great successes, such as they were, of this twilight war were largely in the kinetic field: killing the enemy, arresting them, getting local proxies to fight them. Hopefully such battlefield successes would deny the adversary their much-needed safe havens and dent the groups' ideological appeal – the luster of victory in the name of God which honed their propaganda. The motivating factors and conditions that fed into the rise of these groups are largely intact (youth unemployment in the Arab countries, for example, was and is among the highest in the world), and their ideological framework – that very modern cherry-picking from foundational Islam as interpreted by key radical thinkers that is Salafism – was beyond our power to change. But the concern that root causes, motivation and the use of language were important was, I think, correct.

While I don't regret my years of working in this field in the State Department, and fully comprehend the continued threat of Salafi-jihadi terrorism, in the guise of ISIS and Al-Qaeda, those years also gave me a healthy skepticism of the role and ability of governments, especially Western governments, to address the challenge, beyond the use of blunt force provided by militaries, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies. There are, of course, many things that governments can do to make these problems worse.

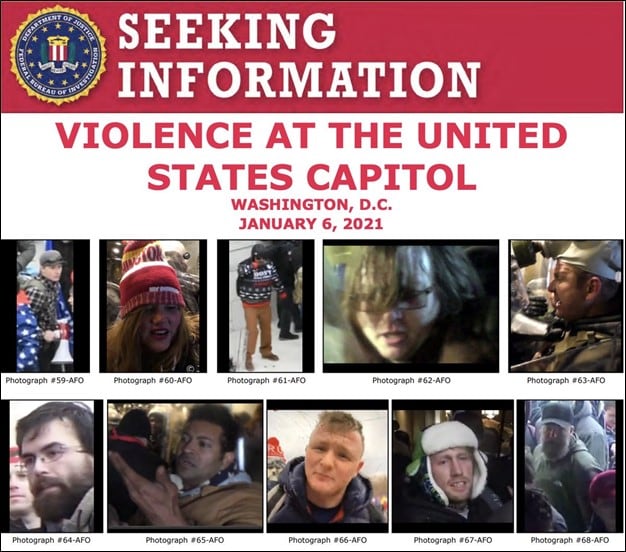

That is why, in the wake of the first anniversary of the January 6, 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol, I continued to be alternately bemused or horrified by the discourse surrounding this event. The New York Times, paper of record of America's elite, editorialized that "every day is January 6 now."[1] Just going by the media coverage and the rhetoric of many politicians, the temptation seems to be to cast the net as broadly as possible instead of as narrowly.[2] There are calls for new laws and greater powers (greater than the already expansive powers that the national security state already possesses). Some combine the danger of anti-government militias and rioters with "conspiracy theorists" and "anti-vaccination activists," and warned that these extremists would now focus on, of all things, "local elections and community activism."[3]

The government has "a limited set of tools for going after domestic extremists." Good, I say. Let them work within the parameters of those not-so-limited tools we already have to punish malefactors to the full extent of the law. MEMRI's own research into domestic terrorism amply documents that there is a very real domestic terror threat.[4] But there is a fine, absolutely essential line between combating a very real threat through law enforcement and recklessly hyping it in the public sphere.

Beyond the follies of the global terrorism conflict, the domestic front features one glaring danger not so visible on the international stage. Here I mean the melding of counterterrorism with partisan political expediency. The temptation is understandable and obvious: the U.S. Capitol rioters were supporters of President Trump enraged by the victory of his opponent. But it is a dangerous temptation to combine a response to real violence too closely with political opportunism. So, a campaign against violent rioters (that have yet to be charged for "insurrection" or as "domestic terrorists") and their enablers needs to be focused and disciplined.[5] The House of Representatives' January 6 Committee has looked very partisan indeed, with the minority party's representatives rejected by the majority.[6] Overall, too much frenzied media flailing and too much incendiary rhetoric by all concerned – a vivid example of the volatile confluence of a contentious, legitimate issue and partisan politics.

Ironically, Biden administration Attorney General Merrick Garland has been harshly criticized – by his fellow Democrats – for being too careful and cautious in prosecuting cases coming out of the January 6 riot.[7] This criticism seems exactly backwards. What is needed is precisely the cool and professional application of law and order, as divorced as possible from overheated and especially political rhetoric.[8]

We live in extraordinary times. In the past few short years, we have seen the following:

SUPPORT OUR WORK

-

A wildly successful campaign of misinformation by a political party against a rival presidential candidate in 2016 being taken up and spun up for years by the government's national security state and the mainstream media.[9]

-

A global pandemic in 2020 which has caused immense harm to society while further strengthening the political and economic stranglehold of entrenched elites, coupled with the expansion of unprecedented power by Big Tech oligarchs.[10]

-

Also in 2020, the worse urban unrest seen in the U.S. in decades, which were also the costliest riots in American history, accompanied by a deep shaking of the intellectual, social, cultural and political foundations of the nation.

-

An ugly riot invading the halls of constitutional power in 2021 during the process of confirming the election of a new President, deeply shaking constitutional order and sending a political shock to the system that reverberated worldwide.[11]

Such times require real discipline, adherence to the rule of law, and prudence in a hothouse age noteworthy for excess, exaggeration and misinformation. This polarization is coming from every direction, amplified by a social media environment dependent on perpetual outrage. Indulging in sweeping ideological hype in such incendiary times is deeply satisfying to some, irresistible to the Zoom-based chattering class, but also deeply self-indulgent. Comparing January 6 to 9/11 and to December 7, 1941 may sound like great campaign rhetoric.[12] But the former led to Guantanamo and the latter to internment camps for American citizens. This is precisely the type of rhetoric to avoid in an already volatile environment.

If indeed January 6 is like those two world-shaking violent events that claimed thousands of lives on their first day, then any extreme countermeasure is on the table. If it was terrible enough but something less than this over-the-top rhetoric, if there are other important factors at play, then a more sober, methodical and less bombastic approach seems indicated (bombastic rhetoric is bipartisan in America today). Less posturing and less of a constant feedback loop of mutual outrage would be a relief for all Americans.

Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI. He served as Coordinator at the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications at the U.S. Department of State from 2012 to 2015.

[1] Nytimes.com/2022/01/01/opinion/january-6-attack-committee.html, January 1, 2022.

[2] Washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/11/22/republicans-are-fomenting-violent-extremism-are-also-hostage-extremists, November 22, 2021.

[3] Thenationalnews.com/world/us-news/2022/01/05/homegrown-extremism-solidified-in-us-in-wake-of-january-6-capitol-attack, January 5, 2022.

[4] Memri.org/dttm

[5] Politico.com/news/2022/01/04/doj-domestic-terrorism-sentences-jan-6-526407, January 4, 2022.

[6] Washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/01/04/january-6-committee-explainer, January 4, 2022.

[7] Newsweek.com/step-step-out-dem-lawmaker-demands-merrick-garland-prosecute-trumpers-jan-6-1644745, November 1, 2021.

[8] Brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/01/05/assessing-the-right-wing-terror-threat-in-the-united-states-a-year-after-the-january-6-insurrection, January 5, 2022.

[9] Economist.com/united-states/john-durhams-indictments-reflect-poorly-on-the-american-media/21806220, November 13, 2021.

[10] Europeanconservative.com/articles/commentary/escaping-the-triangle-rene-girard-and-the-professional-managerial-class, January 6, 2022.

[11] Theamericanconservative.com/articles/things-worth-getting-mad-about, January 5, 2022.

[12] Msn.com/en-us/news/politics/biden-pledges-to-defend-democracy-on-jan-6-anniversary/ar-AASvbNL?ocid=uxbndlbing, January 6, 2022.