An image from Layla Murad's blog

Born to parents who moved from Pakistan to England and settled there, Layla Murad is a student blogger who recently penned a long post describing her experiences growing up in a Muslim social milieu, her own spiritual search in Islamic Sufi teachings that took her to a madrassa in Morocco, and finally leaving Islam in April 2013.

Layla Murad, which seems to be an adopted name after a famous Egyptian-Jewish singer, is a relative of Junaid Jamshed, an acclaimed Pakistani recording artist and singer who embraced the traditionalist Islam of Tablighi Jamaat, a revivalist religious movement that originated in South Asia. In her blog, she explores a number of Islamic concepts as would be expected of a student-age blogger who is searching for spirituality, as well as through the current European debates about the hijab, niqab, and abaya (Islamic veils worn by Muslim women).

From her blog, it appears that Layla Murad and her family came in contact with various Sufis (Islamic mystics) who visited England. However, the most extensive influence on her seems to be of Al-Murabitun, an Islamic movement one of whose leaders is Sheikh Abd Al-Qadir as-Sufi, the former Scottish actor and playwright known as Ian Dallas who converted to Islam in the 1960s. She describes her visit to a Moroccan madrassa maintained by Al-Murabitun for Islamic studies, and a holiday trip during which she danced with Moroccan women, leading to a realization that the power of the Indian film industry Bollywood to unite the world was more extensive than Islam. A major portion of her blog is devoted to the experiences at the Al-Murabitun madrassa.

The following are excerpts from her blog:[1]

"Islam Was Not An Obvious Nor A Quietist Force In My Life; It Was Just There; I Didn't, Nor Did Anyone Else, Think Too Much About It"; "I Contemplated On Whether I Should Cover My Hair In Front Of My Male Cousins, Then Intuitively Gasped At My Absurdity"

"My name is Layla Murad. I left Islam in April 2013. I've always been intellectually curious…. A lot of my infatuation with Islam was to do with my inquisitive nature, and of course the Internet. I was brought up in a practicing but liberal Muslim household. My parents are Pakistanis, both hailing from Muhajir families in Karachi [i.e. immigrants who came from India]. Even the most religious among the Muhajirs are often highly progressive and secular minded when it comes to politics and global affairs. My aunt in Pakistan, for example, who started wearing niqab [veil] after the death of her paralyzed daughter, has the same zeal for Farhat Hashmi (a popular female Wahhabi preacher) as she does for the secular, ethno-centric policies of the MQM [Muttahida Qaumi Movement, a political party].

"Islam was not an obvious nor a quietist force in my life. It was just there. I didn't, nor did anyone else, think too much about it. My parents were the kind of people who would be willing to drop me at a nightclub and pick me up again. Yet, they attributed the good in life to the One God, prayed five times a day, fasted during the month of Ramadan, gave charity. I saw my dad make the Hajj. The Islam that had been passed onto me was the basics: the Five Pillars. But this approach had always seemed bland. I wanted something more.

"Hours I would spend online snooping through Internet forums, websites, and lectures by Islamic scholars – researching how this religion came into existence and what it had to offer. I realized all this time I only subconsciously believed in the supremacy of Islam, not consciously. The Internet was crucial in making me more conscious of the color of my skin, my beliefs, and the fact that the society around me was predominantly non-Muslim. I was completely taken in by the fatwas [Islamic decrees] I had read online by Islamic scholars, all with intensive training in the Islamic traditional sciences, who argued that throughout the juristic history of Sunni Islam, the headscarf has always been an obligation and anyone who argues the opposite is a deviant 'modernist.' Heck, I discovered even the covering of the face was held to be recommended or even obligatory by most medieval Islamic jurists. I freaked out.

"In some ways, the more Islam began to serve a multidimensional purpose in my life (from the way I dressed to the way I thought) the more I became closed off from those around me. My parents were totally against the idea of me wearing the hijab. They just encouraged me to be modest and be reserved when it came to the opposite sex. But I had made my mind up. At the age of 18, I remember uploading a photo of myself in a headscarf on Facebook and the outpouring of support I received. 'Oh mashAllah…, you look so nice,' 'Look at the noor [light] on your face,' 'May Allah grant you Jannah [paradise],' 'SubhanAllah, I want my daughter to start hijab too.'

"I contemplated whether I should cover my hair in front of my male cousins, then intuitively gasped at my absurdity. My maternal uncle, a vehement critic of the headscarf, scoffed: 'The only covering for women in Islam is the burqa. Either you wear that or wear whatever you like. Not this stupid headgear where your ass is still hanging out.' This was during a trip to America, where my cousin was getting married to a handsome non-Muslim (Catholic) guy. I decided I wouldn't wear the headscarf properly until I got back to England. There was enormous pressure on me to look good during the wedding season, and I ended up performing dances with guys I didn't even know.

"Back in England, I reflected upon my time in America. It sounds so petty now, but I was literally going through this phase of 'moral scrupulosity.' I felt bad for not only showing my hair, but more importantly, dancing with/in front of men, blasting Bollywood music, putting too much makeup on. I thought all of these things were forbidden. But these were very personal and intellectual thoughts; I don't think anyone had an inkling of what I was going through. At times, I felt my family (though they prayed and fasted) were too liberal, and other Muslims I knew of (who wore the full face veil and once scolded me for cutting my hair too short) were too extreme. Going to gatherings at my Desi-Muslim [Pakistan/Indian-Muslim] family friends' houses with the headscarf was sometimes embarrassing. Though many modern-but-religious Pakistanis had caught onto the headscarf trend, I was still in a minority. Some couldn't figure out how the same girl who would crack the most jokes at parties, sing and dance, suddenly became so religious."

"The Rockstar-Turned-Mullah Junaid Jamshed, A Member Of The Tablighi Jamaat And A Relative, Once Visited My House; He Was Asked By Mother That If Muslims Don't Study, How Will They Move Ahead? Jamshed, Smugly Replied, 'Why Do Muslims Need To Move Ahead?'"

"I made new friends online who were quite interested [in] dawah [preaching] and learning about the intricacies of the Islamic Tradition, and the 'untold' history of Islam. I learnt that there were certain schools of jurisprudence in Sunni Islam, that there were certain theological schools that made sure we didn't anthropomorphize God like the Wahhabis do unintentionally. In essence, this was the beginning of a sectarian mind, and a mind worried about the finer details of Islam. Though I never categorized myself back then, I'd call myself a 'neo-traditional' Muslim.

"Popular in the West, the neo-traditional movement of Islam is characterized by its advocacy of three main concepts: fiqh (jurisprudence) and maddhab (legal school), aqida (creed), tasawwuf (Sufism/mysticism)…. Its main figurehead in America is Hamza Yusuf, and in the UK: Abdal-Hakim Murad, both of whom are converts to Islam…. I was mesmerized by their understanding of Islam and [their] eloquence. What was of particular interest to me was the way they gave medieval Islam a modern and Western twist and combined knowledge with action: Hamza Yusuf founded Zaytuna College in California, and Abdal-Hakim Murad founded Cambridge Islamic College, both a embarking upon a quest to merge traditional learning with the liberal arts.

"I remember giving a lecture to my family about what maddhabs (schools of Islamic law) are in Islam, and how the ulema (scholars) are so vital to bringing forward a valid interpretation of Islam. My dad actually seemed impressed, but my mum and siblings just looked at me, thinking I'd gone bonkers. Now they make fun of my 'religious scholar' phase and we laugh about it. I remember one of the first signs of a nascent sectarian mind was on the day of the Prophet Muhammad's birth, [celebrated as per Arabic calendar every year on] 12th Rabi ul-Awwal. I shared with others the narrative that it was the Wahhabis – those who deviated from traditional Islam and orthodoxy – who didn't commemorate the Prophet's birthday because they viewed it as an innovation, or bid'a….

"After a little while, I realized how hypocritical I was in searching for spirituality online. I stopped wearing the headscarf, took a break from all the 'Internet Islam' and just concentrated on my studies. Studying philosophy really took a toll on the way I saw religion. I became doubtful of all the claims that had been presented by devout Muslims – despite their attempt in presenting themselves as 'nuanced' and 'balanced.'

"Worried about Pakistan, I became sickened by interpretative Deobandi hegemony in the subcontinent [of India and Pakistan]. Though they were traditional Muslims adhering strictly to the Hanafi legal school, their regressive nature disgusted me. The doors of ijtihad (independent reasoning), as more liberal Muslims complained, had been closed by them. They were misogynists, openly supported the Afghan Taliban (based on the obscure 'Black Flags of Khurasan' hadith), prevented Pakistani public law from being secularized, and were defensive about the madrassa system. The Barelvis of the subcontinent condemned Muslim terrorism, but were just as regressive, prolonging the same madrassa culture.

"The Tablighi Jamaat, a well-known proselytizing offshoot of the Deobandi movement, is very popular in Pakistan and elsewhere in the Middle East and the West. The rockstar-turned-mullah Junaid Jamshed, a member of the Tablighi Jamaat and a relative, once visited my house. He was asked by mother that if Muslims don't study, how will they move ahead? Jamshed, smugly replied, 'Why do Muslims need to move ahead?' I guess he shouldn't have travelled to England by airplane, then. I became tired of religious hypocrisy."

"I Had Stopped Wearing The headscarf… I Thought To Myself, How Extremist Is Allah That Showing One's Hair To An 'Unrelated Man' Is Akin To Disbelief?"; "I Became Disillusioned With Islam; Its Pakistani Form Was Too Bland… Its 'Koran-And-Hadith-Only' Form Was Obviously Too Extreme, Its Traditional Form Was About Living In The Antiquity"

"One day, my dad came back from work and told me he had met a Syrian-Algerian Sufi sheikh (Sheikh Bouafia) through his Syrian-born colleague, Mahmud. My dad couldn't get over the fact that this Syrian sheikh happened to know my dad's long-lost sheikh in Pakistan. It was God's will, he said, not a mere coincidence. My dad told me stories of Sheikh Abu Nasr, a very old man who had escaped sectarian tyranny in his home country, Syria. He was from Hama and travelled on foot to Turkey, elsewhere, and finally settled… in Karachi, Pakistan. My dad, as a very young child, had a special relationship with this affectionate, sweet 90-year-old man, who emanated a deep-rooted spirituality.

"I was fascinated and thought this could be a missing link between me and God. I visited Mahmud and his wife Khudriya's house, where the Syrian Sheikh Bouafia was staying. He was in his early 50s and came to England for medical treatment, but spent a lot of time preaching about the Islamic Sufi path at Mahmud & Khudriya's house. Separate gatherings were held for men and women. As soon as I met the sheikh, his face lit up and said that I would become a big alima [female Islamic scholar] one day. Khudriya, a very fat, pale, blue-eyed woman in a loose Syrian abaya, translated. In front of the other women who had come to meet the sheikh, Sheikh Bouafia told me sing a nasheed [religious song]…. Both the sheikh and Khudriya showered me with compliments….

"My mother and I, at the behest of my enthusiastic father, began to visit the sheikh frequently. My mum was always skeptical. Her spiritual-but-rational brother in Pakistan phoned her not to get involved with these Sufi fraudsters. She felt awkward at the Sufi gatherings. There was an obsession with dhikr (lit. remembrance of God, translitm mystical session), where we would sometimes rock back and forth chanting the 99 names of Allah. Soon, we were both (my mum was pushed by my father) initiated into the sheikh's tariqa, mystical path. The initiation ceremony was bizarre. All the women sitting in the room held hands in a circle and had to touch the same water the sheikh had touched. He claimed this was a Sunnah [traditions of Prophet Muhammad]. Then we had to recite some verses from the Koran and the wird [litany].

"Like my mother, I also began to feel uncomfortable at these dhikr gatherings. My mum stopped going because she thought this kind of sheikh-worshipping version of Islam was completely different to the straightforward Islam of her Pakistani parents. The sheikh told us to renounce worldly pleasures, yet, ironically, he had come all the way from Syria for modern medical treatment. Plus, Khudriya – the sheikh's disciple – had the most beautiful house. Khudriya, once, in a gathering shouted in her broken English and thick Arabic accent when translating the sheikh, 'It is Sharia with Tariqa, not one or the other. You cannot pick and choose! If there is any woman who doesn't wear hijab in public then they are committing kufr [unbelief]! I tell you, kufr! And the sheikh will have nothing to do with her.' I felt sick to my stomach. For starters, I had stopped wearing the headscarf, and even if I did wear one, I thought to myself, how extremist is Allah that showing one's hair to an 'unrelated man' is akin to disbelief? Khudriya and the sheikh peddled the Sufism vs. Wahhabism conspiracy theory: the view that the biggest enemies of Islam are the Wahhabis who call other Muslims disbelievers. That the Wahhabis have taken over Mecca from the traditional ulema who accepted Sufism as a true science of Islam….

"The last straw was when Khudriya and her husband Mahmud themselves had fallen out with the sheikh. They told everyone who had been initiated into the tariqa that another 'better' sheikh would soon replace Sheikh Bouafia. The reasons were not properly disclosed. My dad, who had become spiritually attached to the sheikh, demanded an answer. Mahmud and Khudriya explained to my father that the sheikh was a political man, and that he had connections with Sheikh Ramadan al-Bouti, a Sunni scholar who was siding with the Alawi Assad regime…. The result of this Sufi shenanigan which lasted almost three months was disaster. It also put a strain on my parents' relationship, as my dad became reliant on the so-called powers of the sheikh, whilst my mum thought everything was a load of crap. Yet again, I became disillusioned with Islam. Its Pakistani form was too bland and involved cherry-picking, its Internet form was hypocritical, its 'Koran-and-Hadith-only' form was obviously too extreme, its traditional form was about living in the antiquity, and its Sufi form was another kind of extreme."

On Scottish Convert Sheikh Abd Al-Qadir's Religious Movement Al-Murabitun: "He Successfully Combined Sufism With A Vision For Muslim Politics"; "Al-Qadir Called The Niqab An Innovation, Whilst Other Traditional Scholars Often Praised Women Who Covered Their Faces"

SUPPORT OUR WORK

"Not entirely sure of what I wanted to do at university, I took a gap year and just worked. I became disengaged with my friends, and spent a lot of time philosophizing over what the meaning of life was. I had reached the conclusion that Islam, in its many forms, was pretty absurd, but could not come to reject Islam itself. What was Islam, then? If it is the true religion, then why is there so much ignorance? Why doesn't Islam, as practiced by Muslims, ever make sense? I had stopped using the Internet so much for a while now, but when I did use it, I would often read the books and articles of a man named Sheikh Abd al-Qadir as-Sufi…. a Scottish actor and playwright, initially called Ian Dallas, who converted to Islam in the 1960s…. His movement is known as the Murabitun, named after one of the two historical Muslim Empires in Spain [in English: the Almoravids]….

"He successfully combined Sufism with a vision for Muslim politics. The Murabitun's appeal lay in many things, as they combined knowledge with action. 1) Most of the members of the Murabitun are converts to Islam, predominantly Spanish but some also of black Caribbean origin…. 2) There is a huge emphasis on community and deep criticism of individualism. Without community, there is no Islam…. 3) Sheikh Abd al-Qadir's philosophy was essentially a critique of modern man. It called upon us moderns to truly question the nature of our existence. I began to question the very nature of education itself. What is education? What is its purpose? Had I really learnt anything? What is progress? What is freedom?

"4) Whilst intellectually and philosophically being opposed to modernity, the members of the Murabitun looked modern and attractive. Handsome Spanish converts with well-shaped, small beards and women who wore fashionable clothes. Sometimes they wore headscarves, sometimes they didn't, and when they did, it was literally just a head-covering showing their entire form. Sheikh Abd al-Qadir called the niqab an innovation, whilst other traditional scholars often praised women who covered their faces. Women were at the forefront of the Murabitun movement. 5) Sheikh Abd al-Qadir's call to a revival of 'human nature' was the most appealing aspect of his idiosyncratic philosophy…. 6) Many of the members of the Murabitun had more than one wife…. 7) The Murabitun offered an in-depth critique of capitalism and their solution to capitalism was to establish Islam. Its members argued that our freedom is fake. Behind this fake freedom is the power of global corporate finance that rules the world…. Sheikh Abd Al-Qadir viewed the [European] Enlightenment freedom as a farce.

"8) The Khilafah is obligatory according to traditional Muslims and Islamists alike…. The sharia, therefore, became a 'constitution.' Essentially, the sharia that Ibn Khaldun, Ghazzali, and other Islamic greats spoke of was different to the post-modern sharia of groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Muslim Brotherhood. The Murabitun presented the days of the caliphates and successive sultanates as rules of anarchy with basic law, as opposed to fascist dictatorships. Though traditional Muslims believe in the Khilafah being restored, their approach varies. Most say that the Mahdi (Messiah) will restore the Caliphate. However, the Murabitun have a pro-active approach. And the caliphate means local, traditional justice for them.

"9) The solution to the Muslim Ummah's problems was to 'establish Islam,' as the Koran says. Every Islamic group: from the capitalism-worshipping Wahhabis to the Islamists, the door-knocking Tablighi Jamaat, the esoteric Sufis and the singing folk Barelvis, had deviated, according to the Murabitun. They held that modern Muslims, of all ideological leanings, have so deeply internalized the systems of the kuffar [infidels], yet on the surface they appear to be pious and god-fearing. 10) I had already noticed the Muslim obsession with head-coverings, and finally Sheikh Abd al-Qadir seemed to make sense of it all when he said that the fixation on hijab was symptomatic of how modern Muslims had deviated. The Murabitun's view was that hijab was a distraction from the real issues…. They also berated modern Muslim women for wearing the hijab, covering from head to toe, yet working in banks, and being in servitude of the global banking system.

"11) The Murabitun held that [Islamic economic system] zakat was no longer really zakat because paper money is inherently usurious and therefore haram…. The only way to solve the problem of zakat is to revive gold currency, separate to that of the 'currencies of the Wall Street bankers.' Islamic banking is not Islamic…. 13) The Murabitun's zealous advocacy of the Maliki legal school was probably its main appeal and its main flaw. They argued that this school of jurisprudence was perfect for Muslims in the West because of flexibility, cultural adaptability and the fact that it was successfully practiced in Islamic Spain…. 14) Whilst the Murabitun, like most traditional Muslims, accept the martial Jihad as an orthodox and obligatory part of Islam, they take a definitive stand against suicide bombing, unlike the obfuscated opinions of many Pakistani clerics on this very issue, and genuinely believe that terrorism is a deviance from the true Islamic tradition."

Studying At Moroccan Madrassa: "One Of The Younger German Girls… Was A Skilled Street Dancer; She Found A Lot Of Her Time At The Madrassa Suffocating As She Had [Been] Pushed Into A Religious Education By Her Parents, When Her Real Passion Was For Dance"

"For me, these ideas, in some ways, were revolutionary. Islam was finally answering all my questions. There was purpose, philosophy, politics, solution, and community spirit. And there was scriptural basis for all these things. I found out that the Murabitun have set up a madrassa for boys in Spain and another madrassa for girls in a small town in Morocco. Both were Koran schools, where students memorized the Koran…. I begged my parents to send me there, not telling them completely what the Murabitun were about. I wanted to explore them for myself. My dad was wary. He researched online and found the movement to be cultish. However, after a few months of discussion (argument), I convinced him and my mum to send me. I just had to do this for myself and find out if Islam was worth it.

"Before leaving for Morocco, I met up with a woman whose sister was studying at the madrassa. She was a second-generation white Anglo-Saxon Muslim: her parents were converts. I told her that I have this spiritual vacuum within me and want to experience something new, away from Britain. She told me that it would be a good idea to go there, but not to have such high expectations. She explained to me how the girls who study at the madrassa are really beautiful and all the Moroccan locals love them. So, without notifying any of my friends, or even extended family, I arrived in Morocco in August 2012. There, I met the woman who ran the madrassa, a convert to Islam who left the corporate world in her 20s/30s and went by the name of Hajja Saleema.

"I entered the madrassa, which was basically a house situated in a typical Moroccan alleyway. Altogether, there were seventeen girls studying with me. All were from the Murabitun and initiated into Sheikh Abd al-Qadir's tariqa or mystical path…. Almost all were of Spanish origin; two were Germans and five from England, including myself. The girls greeted me warmly with as-salamu alaykum. The two head-girls (yes, there were head-girls) were around the same age as me: one was a Spanish girl named Habiba Cruz and the other was English girl named Khalila Millington. They were both beautiful.

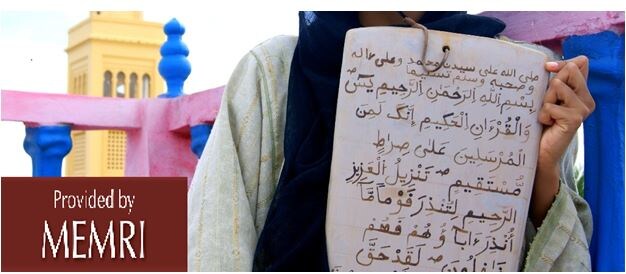

"I got into the daily routine quite quickly. We had to wake up at 6AM, be in class at 8AM until 5PM, where we'd sit on the floor and recite Koran the whole time. My Koran teacher was called Hafidha Jamila, a very petite Moroccan lady in her mid-30s who was completing a degree in Islamic Studies at the University of Tetouan through distance learning…. Her first language was Moroccan Darija, but she also spoke Fusha (standard) Arabic, a little French, and broken English. We would always try to help her improve her English. She was a sweet lady. I recited some Koran to Hafidha Jamila on the first day. She seemed impressed but since I only remembered very few chapters… of the Koran, I started from almost scratch. At the end of 7 months, I had not memorized a lot: altogether I now knew chapters Rahman, Naba, Tariq and the last hizb (in total there are 60 hizb). I loved writing on my tablet. The teacher would dictate to us individually. Completing each chapter felt as if I had really achieved something. I would feel relieved. Whenever someone finished a hizb or a long chapter, we would bake a cake and celebrate. The same happened for birthdays….

"On Wednesdays we would have Arabic classes given by a woman called Rahimu. She was not a good teacher, but a good woman. Thursday and Friday would be our weekend. Our iPods and phones would be returned to us and we were free to listen to music (not exactly like a typical madrassa was it). We could also go out on Thursdays, providing we were back by 7PM. Fridays were a little more hectic as everyone had to wake up early and get ready for the Jummah [weekly Friday] prayer which we would pray inside the madrassa but follow the Imam of the local mosque. Hajja Saleema would live upstairs. Most of her time was spent watching TV and Hollywood films on her laptop or sorting out the legal issues of the madrassa. She would come downstairs to have lunch with us every day. She knew little Koran herself and was the wife of the man whom the madrassa was named after.

"After dinner – I once made biryani for everyone – we had recited the wird. It was the most tedious thing ever. The wird, or litany, was specific to the Murabitun's tariqa. After that, one girl would be chosen by Hajja Saleema. One of the younger German girls who I became close to was a skilled street dancer. She found a lot of her time at the madrassa suffocating as she had [been] pushed into a religious education by her parents, when her real passion was for dance. She said she secretly wished to become a professional dancer and set up a dance studio. All in all, most these girls were pretty normal. They were Westernized, sometimes looked down upon the local Moroccan people as not Westernized enough, yet at the same time not understanding why the Moroccan women did not cover up as much as the convert madrassa girls. I remember eating the skin and bone of food we had (as Moroccans do) and the English head-girl Khalila she looking at me disgusted; sometimes asking questions like, 'I'm sure it's the same in your culture, too?'

"Catfights were bound to happen. I remember falling out with both of the head-girls for a few weeks. Overall, the girls were lovely. The Spanish girls made me feel beautiful, always showering me with compliments about my eyes and complexion. In England, I often felt like an outsider – those memories of being bullied at primary school for the color of my skin had still not been resolved – I observed that the Europeans tended to treat my ethnic background as exotic, whereas living in England, there was nothing exotic about being Pakistani. The madrassa and being with the Moroccan people, was like a boost of confidence. A woman, named Malika, used to visit the madrassa nearly every week with a friend. Sometimes, she would come in the entire week. She was around 60-years-old and would recite Koran beautifully. She bought me gifts and would give me the warmest hug whenever she saw me. She was insistent on me giving my number to her. Islam, the sisterhood, the community spirit meant everything to her and this is what the madrassa was providing for the poorer, working-class people in this small fishing town, in some ways."

On Madrassa Field Trip: "[Some Moroccan Ladies] Told Me They Watched Bollywood Films And Knew Of [Actress] Kareena Kapoor; As A Bollywood Lover, I Found That The Power Of Bollywood To Connect People Together Was Even Greater Than That Of Islam"

"In November [2012], we had a small vacation where we travelled to Meknes and the desert [in Morocco]. In Meknes, we stayed at the zawiya of Sheikh Muhammad ibn al-Habib. A zawiya is a Sufi lodge…. The house was antique, old, and dusty, but striking. It was so cold. There was no heating or anything. The only sign of modernity I saw was the tattered stove. The women would even make the couscous from scratch. Sheikh Muhammad ibn al-Habib's wife and the other women at the zawiya would tell us stories about Muhammad ibn al-Habib and how there was a lion, but when he would recite the names of Allah the lion would roar or something. They also told us that Muhammad ibn al-Habib as a child was very pious and would speak to djinns and when his grave had to be moved, it was opened again, but his face was shining.

"The women also told us about their past, how they used to study at traditional Moroccan madrassas and wear the Moroccan-style niqab. They told us stories about the Day of Judgment over coffee, mint tea, and biscuits: how there would be a line sharper than a needle we had to cross… but I never believed anything they said. Did I feel like it was miraculous or spiritual? I don't know. It just felt nice to be there. I didn't believe in any of the mysticism stuff we were being told about. I failed to see the connection between saint worship and Islam scripturally. It seemed the Murabitun relied too much on the interpretation of their own scholars, intuition, and continually peddled the Sufism vs. Wahhabism narrative. There was less mention of the Prophet, and more mention of the Sheikh Muhammad ibn al-Habib and, of course, their leader Sheikh Abd Al-Qadir as-Sufi.

"In the desert, we spent time with members of the Murabitun who were studying with the 'sheikhs of the desert.' Life in the desert was so simple. Meknes was only simple in the Zawiya itself; otherwise it was a functioning city with hospitals, shopping centers, etc. The clear blue sky, soft sand, mud houses built around palm trees… how could I ever forget? The women of the desert, wrapped in their large sheets, were so hospitable, free, and loving. They made the most delicious food. I had this instant connection with them. Some of them told me they watched Bollywood films and knew of [actress] Kareena Kapoor. As a Bollywood lover, I found that the power of Bollywood to connect people together was even greater than that of Islam. We had a dance night too when the women of the desert invited us to their houses for a good-bye meal. I borrowed this bright blue sequin dress and danced to their old-school Moroccan tunes played in a dusty old cassette player. The kind ladies also applied Moroccan-style henna to our hands.

"We also spent time at famous sheikh's house in the desert. He welcomed us into his house with, 'Ahlan wa sahlan', and we were whisked away to the women's quarter. We were, yet again, served delicious food, spoiled with Moroccan mint tea and a whole host of deserts. We sang qasidas and recited the wird the whole time. It got a little frustrating after a while. The elderly ladies, covered in white sheets, really enjoyed our company. They knew a lot of the wird and qasidas off by heart. As soon as the eldest lady entered the room – like the matriarch of the house – everyone went over to kiss her hand and take her blessings.

"All the girls were mesmerized: excitedly whispering to each other about the spiritual authority of this woman. She was a big lady; olive-skinned and kept praying for everyone. I just didn't see what the fuss was about. I secretly thought to myself: I never want to be like this in spite of the overt piety. What was so special about these 'pious ladies' over my own grandmother, anyway? Had my grandmother been sinful for learning to speak English, wanting to be educated, and embracing modernity? The visit to the madrassa was a particularly interesting part of my experience in the desert. It was for both boys and girls, but obviously segregated…."

"The Murabitun Openly Recommended Polygamy As The Natural Way Of Life; Some Of The Girls' Fathers Had More Than One Wife And They Told Me About The Problems It Caused And How Their Family Lives Were Disrupted"

"The Murabitun openly recommended polygamy as the natural way of life. Some of the girls' fathers had more than one wife and they told me about the problems it caused and how their family lives were disrupted in some ways. I remember the Moroccan man in his 30s who had a basic education (he could speak English) and spent time with us in both Meknes and desert… almost like a guardian. He always smiled at me, in a perverted way. Everyone in the madrassa really looked up to him.

"Whilst the Murabitun approach to gender relations was much more open-minded than other traditional Muslims, there was still this definitive stance that 'a woman is a woman' and 'a man is a man.' The man was allowed to objectify the woman. I wondered why women couldn't do the same. There were around ten guys from the Murabitun movement studying in a traditional madrassa in Fez and they came over to stay at our madrassa. The head-girls told us to cover properly as 'young men are about to come to the madrassa and would feel uneasy!' The girls were obsessed and dressed up a lot. This was contrary to the 'normal' gender relations of my own family. Indeed, cousin marriages were not uncommon but there was no 'oh the men are coming, cover yourselves' kind of mentality. I felt objectified even more with the hijab.

"We had a big end of year dhikr ceremony where many men also attended. The event was segregated by a curtain, but everyone could basically see one another. People were doing the hadhra, which is where you stand up, rock back and forth, and chant the names of Allah. I was literally scarred for life. The entire dhikr was like a matrimonial service, anyway. Most of the girls in the madrassa had been in relationships with guys before. Some, after coming to the madrassa, were shocked when they discovered kissing before marriage is forbidden.

"Despite the Murabitun's annoyance over the fixation on hijab, the girls at the madrassa were generally obsessed with how they wore their headscarves, what color would match their clothes, how much they needed to cover for a specific occasion, whether or not to wear the Murabitun-style headscarf or wear it the 'proper' Muslim way, etc. For the head-girl Khalila, the headscarf seemed like the most important thing in Islam: 'OMG, you can see your hair!' 'Will you ever wear hijab when you go back to England?' 'Did you know: in the Maliki maddhab, covering everything – including feet – except for the face, is obligatory?' 'Layla, don't use us as a blueprint for the Maliki maddhab, haha!' 'The only thing I've ever done wrong in the past is not wear hijab since the day my periods started. Other than that, I've always been a good girl.'

"'Student X, wear your hijab properly! We are madrassa girls!' 'Hafidha Jamila, did you know that girl Zahra that came here last year from Spain? She is studying art at university, she can't even wear hijab anymore. Everywhere there is kufr [unbelief]!' 'Hafidha Jamila, me, X, Y, Z are the only ones that wear hijab. Did you know Layla doesn't wear it, either?!' 'Layla, does your mother wear a scarf? – No. –What? How come?!' Do Pakistani women wear headscarves?' I never knew how to respond to these hijab comments. I'd just shake my head, inside, feeling this burden of skepticism. Often Khalila wouldn't even take off her headscarf in front of women."

On Anti-Modernist Teachings At Madrassa: "Despite The Fact That We Had A Washing Machine, We Were Encouraged To Wash Our Clothes By Hand; If Modernity And Science Was Just That Bad, Then The Madrassa Shouldn't Have Had A Washing Machine, Stove, Or Fridge"

"I wrote in my diary: Promises to myself – do not be brainwashed; memorize at least the last hizb; don't lose critical thinking; modernity is amazing. The Murabitun were philosophically against the Western notion of progress and scientific materialism. Despite some of the Murabitun figureheads having degrees in mathematical physics and whatnot before converting to the 'natural way' of Islam, for them, university education was pointless and taught kufr. But the rejection of 'Western' or a rational education had a detrimental effect on these girls, who had been brainwashed into believing in the 'default truth' of their movement:

"'It's the Jews.' 'The Jews own everything!' 'What the frig, man, why can't we get over the Holocaust.' 'I hate how when someone does something wrong, it's okay, but when a Muslim does it, it's a big deal.' 'OMG. Who was the guy that was a really good person and was hanged? –Saddam Hussein? Yeah, him! He wasn't a good person. He was like Osama bin Laden. –Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein are the same thing.' 'India was in Pakistan.' 'Khalila once tried to subtly endorse the Murabitun's call to gold. She said that when Churchill returned Britain to the Gold Standard (1925), it was great for the economy. I just nodded my head, imagining myself doing about a hundred face-palms.'

"The regressive nature of the Murabitun stood out to me when Sheikh Ali Laraki visited the madrassa. He gave a speech concluding: 'Muslims went to the West for dunya [worldly things], but you (students) are coming back to the Maghreb for the Deen [religion].' Instinctively, I found this statement reprehensible. Had I took on his worldview, it would mean my own parents who came to England for a better life were 'materialistic': only living for the worldly life. What was wrong with the worldly life, anyway? The truth was Sheikh Ali Laraki's own daughters were obsessed with celebrities and he himself divided his time between UK, Paris, Cape Town (oh the West!). He remarked, 'The people of Morocco are simple.' Yet they still rely on the modern basic needs of hot water, gas, and electricity. Science actually works. Do neo-spiritualists condemning the worldly life have any physical solutions? Oh, but the Murabitun did have a solution: the revival of gold currency.

"The failure of neo-spiritual and anti-modernity philosophies became evident to me when we had to evacuate the madrassa twice because of fire. Smoke began to come out from the fuse box in the entrance, only to realize in a matter of seconds that the madrassa had almost lit on fire. As we evacuated, most of the girls were uncovered and some had to run to the local mosque in their leggings/t-shirt to call for help. The entire neighborhood came out to help us. Looking for the good in the situation, the head-girls pointed out that we wouldn't have even met any of these lovely neighbors had it not been for the electrical fault. All the girls sighed al-hamdulillah (praise be to God).

"I didn't want to cry but ended up crying. Most of the girls comforted me, thinking I was freaked out by the fire. They began to chant the wird (litany) and sing qasidas. I was like 'what the actual f***,' I was crying because I realized the importance of worldly knowledge over so-called 'sacred knowledge.' If Islam was 'established' politically, it wouldn't do anything for the people. Islamic knowledge and neo-spiritualism does not save people's lives: it does not fit a simple electric wire into the fuse box of a house. Science works. But we kept being told that scientific materialism was wrong. Hajja Saleema told us that the fuqara & sheikhs of the tariqa had spoken about the dire consequences of the 'hidden shirk [polytheism].' This was when we attribute things to anything other than God. For example, if we are eating food, then it is not the food that has fed us, but Allah. Though the concept in itself was powerful, I found it hypocritical, and very difficult to accept.

"Despite the fact that we had a washing machine, we were encouraged to wash our clothes by hand. If modernity and science was just that bad, then the madrassa shouldn't have had a washing machine, stove, or fridge. Rarely do (devout) Muslims seem to invent these things, anyway, [they] use them all. The worst aspect of the rejection of (modern) science was the Murabitun's aversion to modern medicine and promotion of 'alternative medicine' – what they believed to be Islamic medicine. I was ill for some time and visited the doctor – much to their dismay – who gave me an inhaler. One of the girls argued that inhalers gave her mother arthritis. I remember Khalila reading out loud from The Medicine of the Prophet, by the medieval scholar Imam Suyuti. The 'Hadith of the Fly' (disproved by science) was an interesting one. Khalila became worried about the 'fact' that the Prophet forbade the use of milk and fish together, complaining that Spanish food often was guilty of this."

"One Of The Girls [At The Madrassa], Who Was A Gothic Punk Rocker Back In Spain And Had Had A Few Queer Encounters…; She Was Often Mocked For Being 'Different'"; "The [Murabitun Followers'] Anti-Shia, Anti-Israel, And Unintelligent Banking Comments Did It For Me"; "Moroccan Jews Can Live Here [In Morocco] But Not Christians Or Shias"

"I had already anticipated the cult mentality, but it became too much when they would begin almost every sentence with, 'The sheikh (Abd al-Qadir) said…' and they would specifically talk about their own community all the time. For example, when discussing any human being, the first question would be, 'Is he/she from the community?' They were also obsessed with the Maliki maddhab and its medieval rulings. Though this was obvious in Sheikh Abd al-Qadir's books, I thought it may not manifest itself in real life conversations so much, but it did:

"'Yes, Maliki is the best maddhab. The Hanafis aren't bad. But Malikis are the best.' 'I swear in parts of England, there are only Wahhabis. Malikis are the truth!' 'Oh my God, our [Murabitun] mosque in Norwich is the best mosque. All the other mosques are rubbish.' I quietly observed.

"Moreover, there was a bias against Shia Muslims. I was not from a sectarian family. Though intermarriages were not common in my Sunni family, they weren't looked down upon either. Once, Khalila was discussing with the girls about the Murabitun community and who is married to whom. For political reasons, someone from their community had married a Shia woman. Khalila remarked: 'He's married a Shia. They're not even on the Deen. They actually believe Ali is god. They're kuffar [infidels].' I felt stick to my stomach.

"One of the girls, who was a gothic punk rocker back in Spain and had had a few queer encounters, as one of the other Spanish girls told me. She was often mocked for being 'different' by the girls. One day, when she was listening to gothic music and had been roaming the streets of Morocco with her mother – both without the hijab – she was scolded by the English head-girl Khalila: 'Remember, we are Muslims! We have to look like Muslim women. We have to have good adab (manners). Get real about Islam! Don't be like kuffar women. We have to have pride about being Muslim! All you girls who don't wear a scarf yet, wear a scarf when you go back to your homes in Spain and elsewhere. At least dress a little modestly, but do wear a scarf! Look at me, it's not that difficult! I wear one! And in England, no one says anything to me. Do Muslims… tell the truth? Yes. Do Muslims listen to bad music? No. Do Muslim women cover themselves? Yes. Do Muslims buy stuff from Israel and the Jews? No! Do we support the banking system? No!'

"The anti-Shia, anti-Israel, and unintelligent banking comments did it for me. It made no sense, anyway, since many of Khalila's (and the other girls') headscarves and clothes were from H&M, Top Shop… and various other labels which are all a product of capitalism. The more and more I learnt about the Murabitun, the more I cherished my own brain. I was able to think freely, and many of these girls weren't. My questions became limitless. I didn't understand how it was possible for my Koran teacher never to break her wudu [washing before prayer]. I didn't understand what was so wrong with science. I didn't understand why I couldn't ask any questions in the madrassa. I didn't understand why god would care if we covered our feet during prayer or not. I didn't understand how our prayer would be invalidated if a bit of our hair was showing. Are humans making history, or is Allah? Why has the Muslim obsession with hijab reached unimaginable levels? Why does the Koran allow men to 'beat' women (4:34)? Why do people lie that the word doesn't mean 'beat', when it clearly does? Why does the Koran always refer to men? I cried to Allah nearly every day during night prayers to just send me a sign.

"Then I met Hannah. This was a girl I had met outside the madrassa in the music school. I had lunch with her and she was a typical Westoxified, non-religious teenager. She had lived in Canada for six years with her mother, and intended to go and study there. For six years now she had been playing the guitar, piano, and singing for longer than that. She was amazing: Rihanna, Lady Gaga, Arabic songs… you name it. Her friend, who wore a headscarf, performed an Evanescence song in front of me and then both sang Whitney Houston together. Both girls wanted to become singers. 'Can you teach me English?' Hannah would insist. Wanting to know more about the political climate of Morocco, I asked her if she liked the King (whose picture was on everyone's wall in Morocco, including the madrassa), she replied: 'Everyone likes the King! Like, some don't but like most do. Like. he's okay, but sorta like fat. Hehe.' We spoke about minority rights, and she said, 'You know there's like two things, like Shia and Sunni? Well, if you're Christian or Shia, you can't be Moroccan. You have to leave. Moroccan Jews can live here but not Christians or Shias. One boy in my class… was Christian, but told me not to tell anyone otherwise he'd be taken away. He had to sit in Islamic studies classes.' I wondered what they taught in the mainstream Moroccan Islamic studies syllabus. 'Right now we're learning about community spirit and values.' I realized how cut off this madrassa experience and the ideology of the Murabitun was from the realities of Morocco. The conversation with Hannah only consolidated my doubts about Islam."

"When Someone Does Try To Bring About A Liberal Interpretation [Of Islam], They Are Often Accused Of Blasphemy And Apostasy; This Is Not A New Thing, And Has Manifested Itself Throughout The History Of The Islamicate"

"I needed to talk to someone, so I went to the Internet café and tried to get in touch with a guy named Luke who I had befriended a long time ago on Facebook, but later lost contact. Based in the U.S., he was a convert to Islam who was familiar with the works of the Murabitun. I had no one else to share my thoughts with and I found out that Luke, after nine years, was also questioning Islam. My exchanges with Luke had had a profound impact on me. I thought now was the time to study Islam critically for myself and find out whether it was true. I ordered a few books and began to look into the Koran and Hadith directly. The Koran had so many contradictions. One minute Allah was merciful, the next minute he was cursing the disbelievers. I found that Muslims tended to quote hadith that suited them, but never mentioned any hadith that were completely absurd, even when their 'chains' were 'authentic.' The neo-traditional Islam was absolutely wrong in presenting to the Muslim youth this one and only 'orthodox' view of Islamic history: that everyone followed a madhhab and accepted Sufism, etc. It was parochial and obscure.

"I read [British Muslim author] Ziauddin Sardar's book Desperately Seeking Paradise: Journeys of a Skeptical Muslim, and could relate to his description of the Murabitun movement, who coated Islam in anti-modern, anti-capitalist philosophy, but never looked at the philosophical roots of Islam itself. In other words, its rise, fall, historical events were never studied critically. The traditional Muslims argued that Islam must be seen through an 'Islamic worldview' to make sense, but this was not good enough for me. Where Islam was lacking, they told us ‘context.' Where context was lacking, they told us just to believe in Islam. I looked at the society around and Islam seemed superfluous. I noticed that the Islam I had grown up with was not interested in proselytism or anything of that sort. My parents were pro-progress; they weren't overly philosophical and lived with the times. Granted, it was a cherry-picking approach, but this is how religion naturally evolved.

"In fact, the only reason the Murabitun were able to successfully establish a madrassa in Morocco was for that very reason. Moroccans were not terribly religious and were, for the most part, secular-minded. Though there are human rights abuses and Shias and Christians face discrimination, the king has done a great job of controlling Islam within Morocco, empowering women, which makes it one of the most stable Muslim-majority states today.

"Islam is always [treated as] superior to culture, no matter how much Muslims argue that Islam enriches culture. Islam acted as a deterrent to me immersing myself in my Indian roots. I always admired the Eastern traditions and their rich culture of dance and the arts. In Islam, at a textual level, enjoyment becomes limited. When someone does try to bring about a liberal interpretation, they are often accused of blasphemy and apostasy. This is not a new thing, and has manifested itself throughout the history of the Islamicate. The punishments for blasphemy, apostasy, fornication are worrying, and the fact that many Muslims feel that denouncing these as akin to apostasy itself is even more worrying.

"In the end, I came to the conclusion that Islam was just like any other religion, in the sense that it could be explained naturally. All these interpretations were man-made. Though science has been one of the main reasons why Muslims tend to leave the religion, my reasons for leaving were based more on a personal exploration of the way Islam is practiced. Indeed, I later learned that the so-called verses on embryology in the Koran and its verses on the 'seven heavens' are taken from Galenic and Ptolemaic natural philosophy. Islam's textual incompatibility with modern science only crystallized my doubts. Through my experience, I learnt that Islam's mystical traditions, which are often romanticized, can be as problematic as more literalist interpretations. Now that I think back, it seems surreal that I went this far to discover the veracity of my faith. I'm in a better position, intellectually, than I ever was before. We all search for clarity, and even though I still believe we may never know everything, I know something, and it feels good."

Endnote:

[1] http://desperatelyseekingparadise.wordpress.com/2013/12/28/how-and-why-i-left-islam/, accessed December 28, 2013. The original English of the blog has been mildly edited for clarity and standardization.