On May 9, 2008, the Algerian e-journal Le Matin reproduced a press release by Reporters without Borders stating that the Algerian government had refused to allow the popular pan-African weekly magazine Jeune Afrique to sell its May 4, 2008 issue in Algeria. While the government offered no explanation for the move, Reporters without Borders said that the article the government found offensive was Farid Alilat's "Le grand malaise" ("The Great Malaise"), which dealt with the killing, by police, of 126 civilian Berber protesters in the Kabylia region in 2001 – events collectively known as the Black Spring. The Black Spring demonstrations were sparked by the police killing of high school student Massinissa Guermah; unrest quickly spread throughout Kabylia, with protesters demanding police accountability, official recognition of the Berber language (Tamazight), and civil rights.

In response to the ban, Jeune Afrique posted the article on the free section of its website. Following are excerpts:[1]

"Wrapped in her traditional Kabyle dress, her face full of wrinkles, her eyes red from having bemoaned the loss of her child for so long, she clutches his photo to her heart. [Her husband], his face also showing the marks of time, his body as dry as an old emaciated olive tree, has a vacant look on his face.

"For Djohra and Ahcene, and for all the Irchene family, life stopped its course on Friday, April 27, 2001, at exactly 3:30 PM. That day, their son Kamel, 27, who was protesting alongside a hundred or so youth in front of the Azazga police station, 35 kilometers east of Tizi Ouzo, was hit by two bullets, one in the thorax and the other in his left arm.

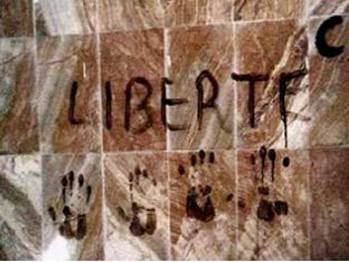

"A short time before succumbing to his wounds, Kamel found time to write the word 'liberty' in his own blood on the grey wall of a village café. Now covered with plexiglass, the graffiti has since become the symbol of the revolt that set Kabylia ablaze in the spring of 2001.

SUPPORT OUR WORK

"The Irchene family is still looking for answers to their questions. Who killed Kamel? Where is his murderer? What is the judicial system waiting for in order to deal with the case file that has been sitting on the desk of the preliminary hearing judge in Azazga?

"Ahmed, a brother, said: 'Since that ominous Friday, we refuse to mourn him [passively]. How can our hearts be calmed when we know that his murderer is free? The authorities gave us money and even offered work. Don't they know that only justice can diminish our pain?"

"Seven years after the riots that drowned the region in fire and blood and cost the lives of 126 people, the families are still demanding justice for their dead. With the exception of the murderer of Massinissa Guermah, killed April 18, 2001 at the police station in Beni Douala [i.e. Ath Douala], no suspect from among the security forces has been given cause for worry. True, some policemen were relieved of their duties, and others were transferred. Nonetheless, says Belaid Abrika, spokesman for the Archs (city and village committees representing the population),[2] the state assumed a formal engagement to shed light on these tragic events:

"'There is no lack of evidence and witnesses with which to confront them,' he said. 'We have formally identified 20 killers. Witnesses and wounded individuals appeared before the preliminary judge to give the names and physical descriptions of the policemen who opened fire. But to this day they have not been made to confront [this evidence]. Why?'

"There is no rule of law,' Ahmed Irchene responds. 'Our inner conviction is that they do not want to judge the murderers.' Mourning, impunity, the feeling of injustice – seven years later, the Kabyles' memory [of the events] is still raw.

"On paper, the crisis has been settled. Officially, it ended when the Archs and the government, then headed by Ahmed Ouyahia, signed the protocol agreement under which the state undertook to satisfy all the demands in the El-Kseur Platform – in particular, those relating to granting official status to Tamazight [the Berber language], the prosecution of those responsible for the murders, the payment of indemnities to the families, and the granting of the status of 'martyr' to the victims of the repression.[3] More than three years after the signing of this famous agreement, the results have been meager..."

Endnote:

[1] www.lematindz.net, May 9, 2007; www.jeuneafrique.com, May 4, 2008; image: www.makabylie.info/?article416.

[2] For a September 2006 statement from the Archs, see MEMRI Special Dispatch No. 1308, "Algerian Berber Dissidents Promote Programs for Secularism and Democracy in Algeria," October 6, 2006, Algerian Berber Dissidents Promote Programs for Secularism and Democracy in Algeria.

[3] In official Algerian parlance, 'martyr' (shahid) usually refers to those killed in the war of independence, and more generally to anyone killed in action. The families of officially recognized martyrs receive benefits from the government.